Rick Graham PMP

Ahead of its January 2021 meeting in Davos, the World Economic Forum published its Global Risks Report 2020, based on the input of 750 experts and outlining the biggest risks faced by economies over the next 10 years.[1] Infectious disease was ranked as 10th biggest risk in terms of impact, and didn’t figure at all in the top ten by likelihood. And if the WEF didn’t see a risk coming, then what hope do we have?

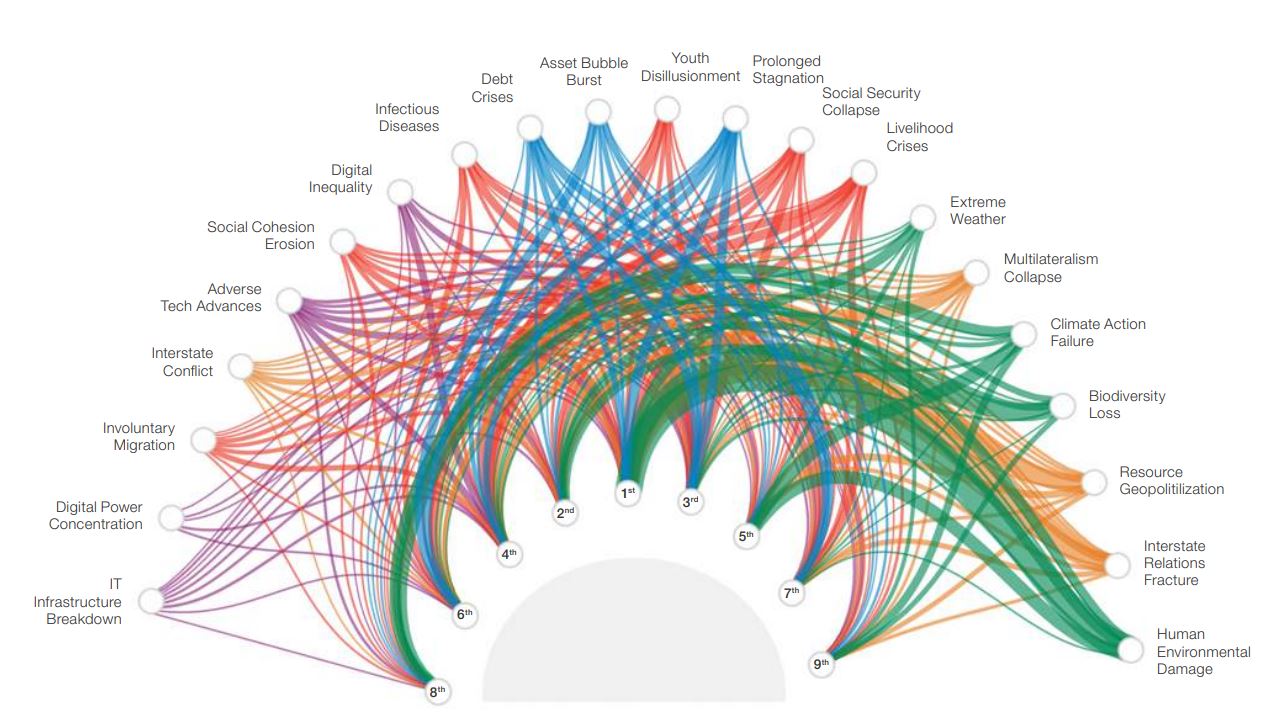

Even in the 2021 report, the risk of ‘Infectious Disease’ whilst reaching 1st position in terms of impact, reached only 4th position in terms of likelihood (huh?).

Whatever the case, it’s certain that recent events have forced us to reassess how we do risk management. The biggest challenge is that in this volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) business world, the simple approach that we once took to risk management is no longer sufficient. This article aims to summarise some aspects of risk management that we should be thinking about, whether we are a project, program, portfolio or business manager.

- Make sure that all relevant risks are identified, even if they are outside of project scope.

Surely no-one could have predicted Covid-19? Well, yes they did! After a local arts event was cancelled in my home town it was discovered that their insurance (taken out November 2019) excluded compensation for cancellation caused by ‘SARS, MERS, Influenza or any virus related to these’- such as Covid-19. We can probably learn a lot from the insurance companies (as well as the bookies!).

So what can we do? The easy answer, although hard to implement well, is to make sure that we use a systematic and integrated process, based on all relevant inputs. It’s not surprising that most risk management training spends so long on this subject.

- Remember that ‘event’ risks may not be the biggest source of uncertainty.

Reporting on the 6 month delay in a major construction project, the project manager stated that there had been a 2 month delay caused by a strike, a 1 month delay caused by unexpected bad weather, and the remaining 3 months was ‘normal delay’. This sounded humorous at first hearing, but the project manager was only reporting the reality for many projects. Yes, there are event risks that should be in the risk register, but uncertainty comes from many sources, a significant one of which is the quality of front-end loading (in this case evidently underestimating).

Event risks are relatively straightforward to manage with a standard ‘PMBoK’[2] type process, however other uncertainties are much more difficult, being multi-factorial in nature. As an example, in a recent oil and gas project there were over 800 documented changes. Over 90% of these changes were internal (supplier) design changes. These could have been prevented by rigorous front-end loading, which might have included a prototyping process where design uncertainties remained.

There is a simple starting point: simply avoid confusing event and non-event uncertainty.

- Be careful with likelihoods

Likelihood is hard to assess. Why? Because we can only assess likelihood if we have a representative data source, and project risks are typically one-offs. For example, how can we come up with a likelihood for a change of import duties? Or of a competitor entering the market?

In the absence of data we might use subjective judgment, but this is not necessarily the same as expert judgment. A recent risk review by one of our clients identified the following as their top installation risk: ‘…. wrong tool set is shipped to client site…’, with high likelihood and high impact. The rationale for such an analysis? ‘It happened last time’ – plainly biased and misguided thinking – the likelihood of it happening again I put as close to zero, given the pain it had evidently caused them first time round!

So, to summarise, we should be very cautious with simplistic <Likelihood x Impact = Expected Value (EV)> calculations, even if they are consolidated. Firstly, the EV never happens, and secondly the output is very sensitive to the Likelihood input, which as we have said is ‘probably’ not reliable.

- Use an Integrated Approach

The direct impact of an event risk may be easy to estimate, but what about the wider impacts?

A recent project to develop a campaign for a new pharmaceutical was so successful that it won a marketing industry award. The only problem was that, because of competitor entry into the market, the new drug failed to sell and was later withdrawn. So, whose risk was this? The project manager, the programme manager, the business manager? Who knows? Successful organisations manage their risks across projects, programmes and benefits realisation by integrating risk management at a portfolio management level, and integrating this at organisational risk management level.

The importance of this is not only to ensure that all risks are understood and managed, but also to ensure that inter-relationships between risks are fully accounted for. The failure of a new technology in a single small project may not be a problem, but if we’ve incorporated that technology into all our projects… .

- You need to build organisational resilience

Resilience is for the ‘unknowable’ unknowns. Part of this is structural – for example defensive measures may include provisions for data/ IT security; progressive measures might include supply chain contingencies, based on accurate mapping as well as business continuity plans.

But crucial within resilience are flexible processes, the right leadership, skilled and empowered project teams, clear lines of engagement with stakeholders (in the light of emerging risk) and an agile (that is ‘nimble’) approach by the organisation. This must be coupled with clear contingency fund planning.

- Risk requires an honest approach

In the worst situations, risk planning becomes an internal political struggle. This can arise as projects fight for contingency budgets, management fights for margin, and finance fights for an EAC (estimate at completion) acceptable to the board. Where the organisation does not openly address risk, destructive behaviours (such as creation of hidden contingencies) may arise. Good risk management requires an honest and integrated approach as to how risks are planned and managed.

- Things happen in threes.

Of course, I’m not literally serious,[3] but it should be remembered that the historical ‘worst case’ was worse than the previous worst case. ‘Hoping’ that something won’t happen is not sufficient. We have to face the true reality of uncertainty in our projects and programs despite sometime pressure to downplay this in the interests of expediency.

The good news is that the tools exist, although they’re generally more sophisticated than we have been used to (for example Monte Carlo), but what is more important are the skills, leadership and the realisation that different approaches are necessary in our new VUCA world.

Is there such a thing as too much risk planning? Maybe. But there is definitely such as thing as too little!

[1] World Economic Forum, The Global Risks Report 2020, 15th Edition.

[2] Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (6th edition 2017).

[3] Touch wood!

No responses yet